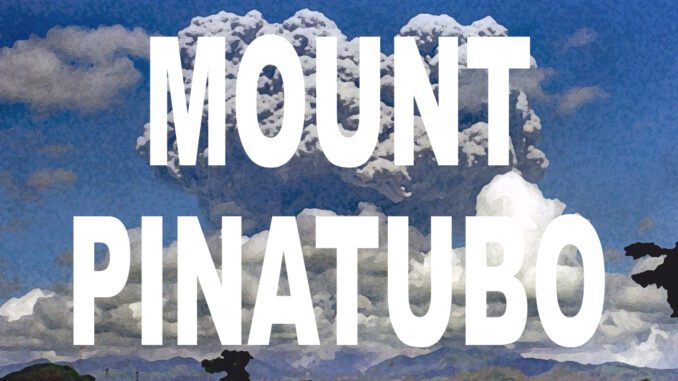

In the middle of June 1991, Luzon, the largest island in the Philippines, was rocked by the eruption of Mount Pinatubo.

After 500 years of lying dormant, this sleeping giant began to show signs of stirring in April of that year, as it sent out large puffs of steam. Until a few years previously, nobody had even suspected it was still active. So when it finally – and spectacularly – erupted in 1991 it took everyone by surprise. Although earthquake monitoring in the region had, thankfully, alerted scientists to the possibility of volcanic activity.

The blast itself was recorded as the second largest of the 20th century, second only to the Novarupta in Alaska in 1912, ten times larger than Mount St Helen’s.

The End Of The World?

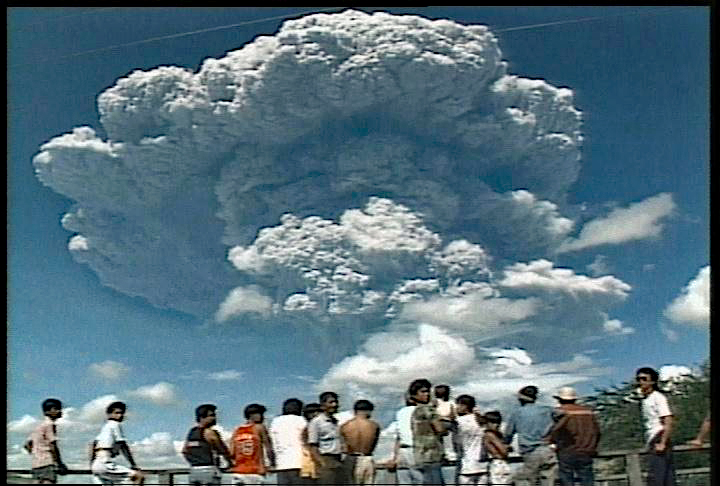

Over time, more than a million people had settled on the lush green slopes of Mount Pinatubo, with villages and settlements spread evenly across the area, including Clark Air Base, the largest US base in the Philippines. Once it had been realised that an eruption was imminent, danger zones were designated and those who were within 10 km of the volcano were advised to take action, with nearly 500,000 people evacuated.

Typhoon Yunya – which would have caused enough problems of its own – hit the island at the same time. The two combined events had a devastating effect, not only on the local area, but also around the planet. Those who lived on Luzon would have been forgiven for thinking that their world was coming to an end.

The eruptions started properly in the early hours of June 12, 1991, followed by more massive blasts lasting around thirty minutes that sent columns of ash 19 kilometres into the air. The resulting pyroclastic flow reached as far as four kilometres from the summit.

This, however, was merely an overture to what was to follow.

The next couple of days saw a series of smaller and larger blasts, lasting between three and fifteen minutes, with massive columns of ash attracting huge bolts of lightening due to the immense friction. Seismic activity all pointed towards a devastating crescendo.

At 13:42 local time, an eruption lasting three hours shook the island with multiple earthquakes as the top of Mount Pinatubo collapsed on itself, creating a caldera 2.5 km wide, lowering the summit by around 260 meters. The pyroclastic flow stretched out an extra two kilometres beyond the point it had reached a few days previously.

It was at this point that Typhoon Yunya hit the island, which, combined with the ash clouds, brought complete darkness to the island for about 36 hours. The ash column from Pinatubo at this time had reached as high as 34 km, and it is estimated that the cloud covered an area of about 125,000 square kilometres.

The Aftermath

In spite of the relatively large island population, as well as the fact that Mount Pinutabo had only recently been discovered to be active, the death toll was surprisingly low. The successful evacuation procedure was undoubtedly responsible for saving thousands of lives.

The official death toll was listed as 847, and the majority of these were victims of the combined force of the typhoon rains mixing with the volcanic ash.

The resulting mixture fell on a wide area, blanketing whole towns and cities. An area of about 7,500 km was completely covered in a layer at least 1 cm thick. Up to 9 km away, houses were coated in a concrete-like mix of rain and ash. Houses unfortunate enough to have a long roof span were unable to take the weight. Victims of the collapsing roofs made up a significant proportion of the death toll.

Aside from the deadly pyroclastic flow that swept down the slopes at great speed, another type of event caused further damage to the local area.

Lahars are huge, fast-flowing walls of mud and debris that can cause massive amounts of destruction, choking river valleys and destroying infrastructure. The 1991 eruptions at Pinutabo deposited approximately 5 cubic kilometres of rock fragments and ash on the slopes. During the next four rainy seasons following the 1991 eruption, lahars became a real problem, causing widespread damage. The problem had been worsened by the fact that the slopes were now bare, completely stripped of the vegetation that had been destroyed by the ash and lava.

Reforestation projects were continually hampered by lahars, with over 14,000 hectares of seedlings or newly established forests being swamped by mud and debris.

Ash proved to be a problem, with more than 96,000 hectares of agricultural land severely affected. Around 800,000 head of livestock and poultry was lost, depriving thousands of farmers of their livelihoods. The cost to farming was estimated at the time to be around $52 million, rising to $107 million by the close of 1992.

Agriculture was by no means the only casualty. Infrastructure, communications, power, water, and transport all faced serious problems, with an estimated $142 million worth of damage. Over 8,000 houses were completely destroyed, with another 73,000 sustaining structural damage. Approximately 1.2 million people were made homeless. Bridges and roads were buried or wiped out entirely, and Manilla airport was closed.

At least sixteen aircraft suffered from the effects of ash, with countless others being damaged by sulfur deposits, causing millions of dollars worth of damage.

Global impact of Mount Pinatubo

The effects were not, however, limited to Luzon and the Philipines.

The volcano’s plume reached up into the stratosphere, where it left 15 million tons of sulfur dioxide. The effect of this was twofold, bringing both a drop in average global temperatures of up to 1 degree F (0.6 degrees C) for two years as well as a rise in the stratospheric temperature which may have contributed to severe storm systems over a period of three years.

Rainfall patterns over Asia were disrupted and ozone levels in the southern hemisphere were dramatically decreased It is safe to say that this eruption, though relatively few lives were lost, touched the whole world.

Be the first to comment